HISTORICAL MINIATURES JOURNAL ISSUE NUMBER 12

BY GEORGE GRASSE

|

BUILDING

THE 1:48 SCALE COPPER STATE MODELS' GERMAN AEG N.I (C.IVn) C.9328/16 'NACHTFLUGZEUG'

(NIGHT BOMBER), WESTERN

FRONT, SUMMER 1918

|

|

|

|

This photo of an AEG N.I

shows most of the unique features of this aircraft including 1)

hexagonal camouflage; 2) heightened exhaust stack; 3) upper wing

trestle reinforcement; 4) three-bay wing; 5) circular

observer/gunner turret; 6) landing lights (forward edge of upper

wing at the center wing strut); 7) 150 hp Benz Bz.III engine; 8)

underwing bomb racks (barely visible); 9) observer/gunner's

underwing bomb release lever just outside the cockpit down low

on the fuselage; otherwise, a modified AEG C.IV. In fact,

most of the first batch of production aircraft were known as AEG

C.IVn ('n' for nacht or night bomber). Serial number on

fin is not completely visible but appears to be C.9378/16 of the

first production batch. Crew, unit, and date

of photo unknown (probably late 1917-early 1918). Photo courtesy of

Jack Herris. |

KIT DESCRIPTION

The 1:48 scale WW1 airplane covered in

this issue is

the Copper State 1:48 scale resin cast kit of the German AEG C.IV that is to

be modified into the AEG N.I (C.IVn) configuration. As a reminder, the

designation AEG N.I (C.IVn) refers to the late-war designation "N" for

single-engine, two-seat night bombing aircraft and "C.IVn" refers to the

those aircraft of

the first production aircraft built before the "N-type" designation was created.

The small case "n" was the early designator for single-engine night

bomber.

I have described the basic kit contents

for the Copper State AEG C.IV in previous HM Journal articles and you can refer to them here:

HM Journal Issue 6.

I should point out that many limited run resin kits are not necessarily complete

kits. In this kit, for example, the modeler has to scratch-build a number

of parts including the landing gear axle sub-assembly and struts, gunner's seat,

rudder bar, control stick, wing struts, cabane flat struts, cabane "V" struts,

and various braces internal to the AEG C.IV observer cockpit (but not needed

on the AEG N.I). Also, most resin kits are best handled by experienced

modelers. They are quite demanding.

Not supplied in the kit or otherwise

replaced are a number of

items which I will detail in the step-by-step Construction section below.

I used the following after-market accessories:

Copper State CS0122 German Gauge Set

(PE & film)

Eduard EU9194 World War I Instruments

(PE color)

Strutz brass rods

Aeroclub ACV101 German Observer's

Gun Ring

thin copper sheet

.005 monofilament line for rigging

wires

MODEL TO BE BUILT

This is another model I

knew I would have research authenticity problems for three reasons: 1) photographic evidence history of this aircraft is

sparse largely because so few were built; 2) photographs and/or historical

documentation of a specific crew, serial number, unit,

date, and surrounding circumstances is also sparse; 3) the details of exactly

how these aircraft were used is not available to me in the form of documented

German manual or set of instructions. I will have to infer quite a bit

from the references I have. At this point, I am going with my

interpretation of the photo at the top of this page which I believe is C.9378/16

and, therefore, the 56th AEG C.IVn of the first production batch.

This model requires

substantial number of modifications including a converted engine, addition of the

observer's gun ring, addition of underwing bomb racks, and, most difficult of all,

the modification from a two-bay biplane to a three-bay biplane. All of the

details that make the AEG N.I different from any other aircraft with the

exception of the late-war Sablatnig N.I (of which few reached the Front) will be

detailed further on. The single most outstanding difference between the

AEG N.I and its progenitor the AEG C.IV is the wingspan necessary to carry a

heavy bomb load. Illustration 1 compares the two aircraft in half plan

views.

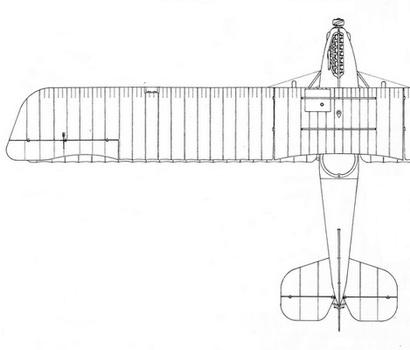

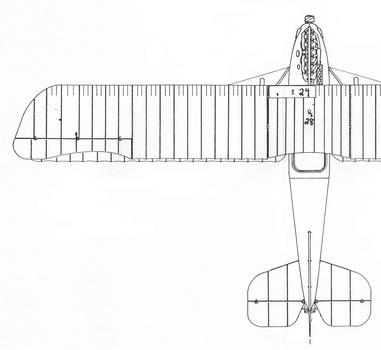

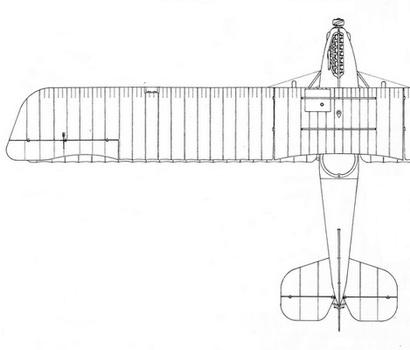

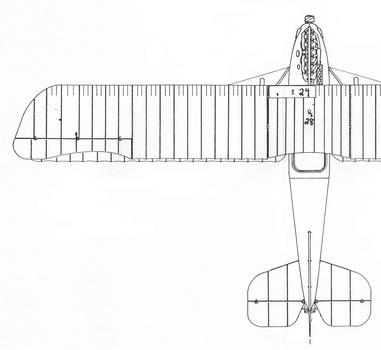

Illustration 1:

COMPARING THE AEG N.I (C.IVn) TO THE AEG C.IV

|

AEG N.I (C.IVn) HALF PLAN |

AEG C.IV HALF PLAN |

|

|

|

The AEG C.IV required two sets (or bays) of wing struts on each

side where the AEG N.I required three giving larger wing area.

Note the great similarity of the two aircraft. Some of the

major differences between the two aircraft are the

observer/gunner's cockpit shape, the right-hand exhaust of the

160 hp Mercedes D.III engine on the AEG C.IV (left) and the

left-hand exhaust of the 150 hp Benz Bz.III engine of the AEG

N.I (right), the presence of landing lights on the small cut out

at the leading edge of the AEG N.I upper wing, and slight

differences to the arrangement and size of the upper wing center

section. Not shown in these images is another substantial

difference and that is the camouflage scheme which will be

detailed further on. |

|

|

|

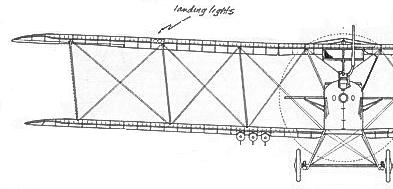

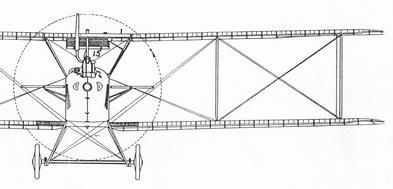

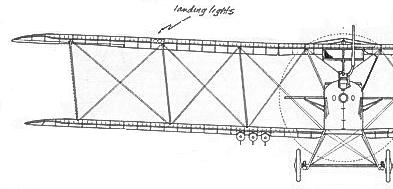

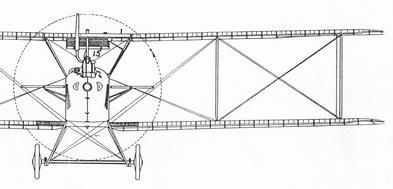

These frontal views show the difference between the two

aircraft. Note how the AEG N.I (left) strut configuration

is slanted. You can see the projection of the

exhaust stack: the Benz Bz.III (left) and Mercedes D.III

(right). One important characteristic is the underwing

bomb brackets for the AEG N.I, each capable of holding one 50 kg

bomb for a total load of 300 kg. The AEG C.IV had a modest

internal load of four 12.5 kg bombs, or 50 kg total. I

marked the location of the landing lights on the AEG N.I.

Night landing accidents were are more significant cause of night

bombing casualties than from enemy action, fighters or

anti-aircraft. |

|

Image credits go to Martin Digmayer whose excellent general

arrangement drawings have appeared in hundreds of publications.

The image of the AEG C.IV was cropped from the general

arrangement drawing appearing in the Copper State instruction

and information packet for the kit, CS1017, of the AEG C.IV.

The image of the AEG N.I was cropped from the Rare Birds article

"AEG N.I (C.IVn)", written by Peter M. Grosz and Jack Herris for

Over the Front Volume 23 Issue 4 produced by the League of World

War I Aviation Historians. |

Illustration 2:

THE OTHER SINGLE-ENGINE NIGHT BOMBER - SABLATNIG N.I

|

|

The only other single-engine two-seat night bomber recorded in

the Frontbestand by Peter M. Grosz is the Sablatnig N.I pictured

at left (photo credit A. Imrie).

1

The firm Sablatnig Flugzeugbau GmbH of Berlin

produced over 200 single-engine two-seater floatplanes for the

aviation arm of the German Navy, Marine-Luftschiff-Abteilung, and

was named after its founder and chief engineer Dr. Ing Josef

Sablatnig (PhD Engineering). The Sablatnig N.I was powered by the Benz Bz.IV

220 hp engine. 2 |

AN ABRIDGED (AND SHORT) HISTORY OF WORLD

WAR I STRATEGIC BOMBING

One basic definition as

given in the Dictionary of the First World War is, "the potential of

aircraft to launch long-range attacks deep inside hostile territory and to

disrupt an enemy's vital socioeconomic process."

3 The only aerial weapon at the beginning

of the war that met these criteria was the dirigible (airship) and Germany was

the only nation that used and added to this force from the beginning. On

the night of 19/20 January 1915, the first German airship raid against Britain

was launched. However, by May 1917, the twin-engine Gotha bombers began

the their strategic bombing campaign against Britain and the airship was phased

out as a weapon due largely to the vagaries of the weather and their

catastrophic vulnerability when hit by enemy fire from improved night fighters

and AAA. To be sure, airships were used by all of the large nations and

they made appearances in nearly all theaters in rather limited scale. The

airship attacks against Britain more or less proved the strategic bombing theory

especially if you focus on "socioeconomic" part of the definition. All

belligerents were convinced of the fear factor and/or the retaliation factor;

so, as much as it was strategic bombing it was also purposeful indiscriminate

bombing hiding under the guise of directing attacks only against military

targets. Now to the aeroplanes.

4

By November 1914 when the

Great War was barely four months old, aeroplane strategic bombing was created,

first by France on 23 November 5 followed in days by Germany on 27

November4. Both initiatives involved official orders creating

bomber units. In France, this was the 1er Groupe de

Bombardment under the Chief of Staff of the GQG or Grand Quartier

Général

(General Headquarters) 5 and, in Germany, Brieftauben-Abteilung Ostende or

BAO, also under the equivalent general headquarters,

Oberst-Heeresleitung or OHL. The German unit, translated, means

"carrier pigeon section, Ostend" (Belgium), the codename for strategic bombing.

A second unit, Brieftauben-Abteilung Metz or BAM, was created and

both were operational on the Western and Eastern Fronts by late Spring 1915 but

operated more as a strategic aviation reserve than a strategic bombing force.

6

Whereas the French actually

deployed bombers, such as they were, and conducted daylight bombing raids across

the Rhine, into the Saar valley, and into Lorraine, all military or industrial targets, the Germans equipped their BAO and

BAM units with two-seater reconnaissance aircraft that conducted few

strategic raids. Rather, the force was used to supplement air strength in

sectors where combat was heavy, either offensively or defensively. By

early 1916, the French had abandoned daylight raids because of high losses due

to the newly developed single-engine fighter and resorted exclusively to night

bombing. The Germans recognized the importance of the strategic reserve

and in December 1915 officially changed the unit designation to

Kampfgeschwader der OHL or "battle squadron" (abbreviated Kagohl or KG) each

composed of six Kampfstaffeln (flights, or Kastas) of six

two-seater aircraft each. 7

Curiously, the German

aviation industry had developed large twin-engined bombing aircraft that were

initially deployed to Kastas in ones and twos to be used as aerial battle

airplanes to assist in "combat" against enemy aircraft. At the beginning of the Verdun offensive in February 1916, the

Germans developed the aerial strategy of "barrage patrol" or sperrflug,

intended to block enemy aircraft from penetrating the German front line and

discovering troop movements, artillery emplacements, and dumps. Two Kagohls were

deployed at the outset of the offensive and attempted to perform their

blockading mission but given varying heights at which enemy aircraft could fly

and the great distances along the front, it was impossible to prevent French

aircraft from performing interdiction, reconnaissance, and fighter patrols.

Kasta two-seaters and the large, twin-engined "battle planes" were

outclassed by the nimble French Nieuport fighters (Types 11 and 14) and it took

the re-deployment of Fokker Eindeckers to Verdun to help defend the air space.

Germany was still having great difficulty in the air all along the Western

Front. The Allies had equal or better aircraft and they had twice as many

available for deployment.

Although the concept of

Germany's

strategic reserve of their Kagohl units had merit, their intended use as

"combat" aircraft was proven false simply by aerial combat casualties and the

increased success of more Fokker Eindecker fighters and, by Spring 1916,

the deployment of more nimble German biplane fighters such as the Halberstadt

D.II. Fighters were the true "combat" aircraft and Germany finally

recognized this. An emphasis was placed on the production of twin-engined

bombers principally built by AEG, Friedrichshafen, and Gotha.

Daylight bombing was the natural method for strategic bombing because it offered

relatively easy navigation and target acquisition. However, as more of the

twin-engined bombers deployed and more daylight bombing attacks were completed,

casualties mounted because more Allied fighters and much improved AAA took

advantage of the bombers' slow speed, lack of maneuverability, and no escorts.

On 7 July 1917, the last daylight raid over England by Kagohl 3 from bases

in Belgium was conducted. On the night of 4/5 September 1917, the first

night raid on London was conducted. The raids on London, day and night,

were conducted by twin-engined Gotha bombers. During the period of their

use in the daylight bombing role from May to July 1917, London area defenses

were built up to such an extent that, simply put, the Gothas were taking

unacceptable losses. 8

AN ABRIDGED (AND SHORT)

HISTORY

OF STRATEGIC NIGHT BOMBING

Night bombing changed the

tactics used to reach, attack, and return from a target. Bombers could no

longer fly in formation for fear of hitting other aircraft in the formation.

Instead, bombers took off singly at timed intervals. They reached their

target and bombed as individual attacker. They returned to base in much

the same manner and, with the aid of a complicated system of flares and flashing

signals, were able to acquire their landing fields who, upon the correct

sequence of signs, turned on the field's landing lights at which time the bomber

turned its landing lights on. However, landing accidents were still a

major problem and accounted for most of the losses.

Night bombing was safer

than daylight bombing and many improvements had already been implemented.

Navigation was aided by the placement of search light beams at known locations

that guided the aircraft on the correct flight path. Engines were turned

off as the aircraft glided on its bombing run thus making it difficult for

ground defenses to pick up the bomber with sensitive sounding equipment.

Cockpit lights, exhaust dampeners, and dark camouflage made the bombers

difficult to see even on moonlit nights. By early 1918, a number of C-Type

(single-engine, two-seater) aircraft were attached to each Kagohl and

they preceded the flight, some being used to verify the weather (leaving quite

early) and others used to mark the target with flares (leaving just before).

Aside from landing

accidents, the scourge of the night flying bomber was searchlight-assisted AAA

and increasingly sophisticated night fighting tactics. When illuminated by

a searchlight beam, the pilot would often put the nose down and bank slightly

left or right. Once out of the beam, the aircraft was difficult to

re-acquire. The Allies countered by reinforcing their searchlight schemes

and trained operators to follow their target. AAA was improved especially

with light, exploding and incendiary ammunition. A full-strength Kagohl

of three Staffels could bomb with 18 aircraft but if one were lost to

night fighters, and one to AAA, and one to landing accident, that's about a 17%

loss for one mission. Germany could build enough aircraft - the problem

was replacing the experienced crews.

AN ABRIDGED (AND SHORT)

HISTORY

OF TACTICAL NIGHT BOMBING

I finally arrive at the

mission of the AEG N.I: tactical night bombing. As might be recalled from

my earlier articles, I discussed the purpose and aircraft inventory of the

Flieger-Abteilung (FA) and Flieger-Abteilung (Artillerie) (FA(A)

units. None of these maintained their allotted aircraft inventory of six

or nine aircraft of a single type or from a single manufacturer. There

were two reasons for this: 1) although Germany could produce aircraft, what was

available at any given time was sent directly to an Armee-Flugpark (AFP

or army aviation park) who distributed the aircraft to their assigned FA and

FA(A) units on a "need to replace" basis; 2) in every FA or FA(A) unit there

were specialized missions that were best carried out by one manufacturers type

than another. In 1917, when strategic night bombing became a relatively

necessary and safe strategy, local commanders at the division and corps level

came up with the idea of having a night bombing capability for tactical

short-range targets on their immediate front that could not be destroyed with

artillery fire.

The contemporary C-Type of

the day could carry 50 kg of bombs; stripped down, perhaps more. It

probably happened that stripping down an aircraft that was otherwise intended

for reconnaissance, artillery spotting, and photography, took away that one

aircraft from those missions. What was needed was a single-engine C-Type

that could carry close to a G-Type (twin-engine bomber) load. Sometime in

early 1917, Idflieg issued a specification that called for such an

aircraft that could carry a minimum bomb load of 300 kg. The AEG company

responded with a modification to their AEG C.IV biplane which became known

initially as the C.IVn. Eventually, this would evolve into the new

designation of AEG N.I. As these aircraft were produced, they were

assigned to certain aviation units operating directly in support of the front

line. More than likely, these units had specially enhanced authorized

inventory of nine aircraft as opposed to the normal six aircraft.

Missions were conducted in

much the same manner as described for the strategic bombers but on a smaller

scale with usually just one aircraft. The first appearance of the AEG N.I

on the frontline inventory (Frontbestand) were 2 aircraft in at the end

of October 1917. For the moment, here is a review of frontline inventory

for the N-Type as shown in Table 1. Note that the data reflects available

aircraft at the units and their aviation parks (AFP). Also note that the

data ends with the August 1918 entry; after this time, German records are

incomplete.

Table 1:

Front Line Inventory of N-Types

9

|

Two-Seater

N-Types |

1917 |

1918 |

|

Feb |

Apr |

Jun |

Aug |

Oct |

Dec |

Feb |

Apr |

Jun |

Aug |

|

AEG N.I |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

31 |

37 |

19 |

7 |

4 |

|

Sablatnig N.I |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

9 |

|

Total N-Types |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

31 |

37 |

19 |

9 |

13 |

Several interpretations of

the data are possible. It seems obvious that the AEG N.I design, based on

the 1915-16 AEG C.IV, was phasing out and the newer Sablatnig N.I was phasing in.

I cannot explain the falling off of N-Types beginning in April 1918 unless

Sablatnig N.I production was delayed. As you might recall, Sablatnig was primarily a

naval floatplane manufacturer and could have had problems getting their landplane night

bomber off the production line. Other questions linger: 1) was the N-Type

classification phasing out anyway? 2) What caused the approximate 50%

reduction in available AEG N.I aircraft from February to April 1918? and, 3)

What caused the 63% drop from April to June 1918?

AEG N.I (C.IVn) DESCRIBED

The AEG N.I (C.IVn) had a

welded steel tube, box-girder fuselage frame covered in fabric. The

extra-long wingspan was of wood construction with two full-span spars and wings

ribs interspersed with leading edge riblets to reinforce the leading edge fabric

from the forces of drag. It too was covered in fabric. During

initial weight tests, the wing failed and a trestle structure was fitted to the

wing center section, fore and aft, as reinforcement; this solved the problem

and, with the three-bay configuration with outward tilting wing struts, became a

key recognition feature of the aircraft. The tail unit was the unaltered

C.IV version of a welded steel tube framework covered in fabric.

Minor alterations at the

nose allowed for the fitting of the Benz Bz.III 150 hp in-line, six-cylinder

engine. The engine exhaust stack was heightened and possibly fitted with a

muffler/flame dampener so as not to reveal the aircraft's exhaust and minimize

its sound at night. With a full 300 kg bomb load, fuel, and two-crew, the

aircraft was slow and had a low operating ceiling but at night over relatively

short distances, this hardly mattered.

The forward firing Spandau

machine gun was deleted as was some other equipment. Structurally, from a

side view, the AEG N.I resembled the C.IV except for the engine and the raised

observer/gunner's cockpit which now had a true gun ring (or turret) for the

flexible Parabellum machine gun, the only defensive armament. Three

external bomb racks were fitted on the underside of the lower wing and an

external mechanical bomb release mechanism was fitted. It ran from the

underwing bomb racks to the outside bottom of the rear cockpit on each side and

terminated with a handle that the observer/gunner could grasp and pull upwards

to release the bomb load.

There does not seem to have

been an effort to improve the landing gear for night operations when a sudden,

unexpected drop in just a few feet could cause a hard landing. Landing

lights were fitted to the upper wing in line with the center set of wing struts.

These plus the aerodrome's lights assisted greatly in night landings but were

susceptible to recognition by roving enemy night aircraft and could attract

unwanted visitors. Additional information is provided in Tables 2 and 3,

below.

Table 2: AEG N.I(

C.IVn) Specifications 10

|

Engine Data: |

150 hp Benz Bz.III |

6-Cylinder, In-line, Water-Cooled |

|

Maximum Speed |

143 km (89 mph) |

|

Climb to 1000 meters |

10 minutes |

|

Climb to 2000 meters |

23 minutes |

|

Climb to 3000 meters |

50 minutes |

|

Wing Measurements: |

Span Upper |

15.24 meters (50.0 feet) |

|

Span Lower |

14.62 meters (48.0 feet) |

|

Chord Upper |

1.65 meters (5.41 feet) |

|

Chord Lower |

1.65 meters (5.41 feet) |

|

Gap |

1.95 meters (6.40 feet) |

|

Wing Area |

41.38 meters2 (445.40 feet2) |

|

Weight |

Fully Loaded |

1609 kg (3,547 lbs) |

|

Crew |

2 |

Pilot and Bombardier/Navigator/Gunner |

Table 3: AEG N.I(

C.IVn) Production Serial Numbers

10

|

Order Date |

Quantity |

Serial Number Range |

Notes |

|

December 1916 |

100 |

C.9323-9422/16 |

Some in this range given 'N' Prefix |

|

November 1917 |

100 |

N.110 - 209/17 |

Unknown how many finally delivered |

According to Grosz in his

Rare Birds article page 361, the actual delivery schedule of the aircraft

to the Western Front is not known because Frontbestand in Table 1, above, does

not start to show availability until October 1917 when two machines are

recorded. All dates on the Frontbestand table are month-ending date (i.e.,

as of 31 October, for instance); and, there is a two month gap between reporting

periods. It is probable to assume that a number of these aircraft were at

the Front in the August to September 1917 time frame but how many remains a

guess. Certainly, a few had to have been issued during this time for

combat field trials.

MODEL CONSTRUCTION

As with all aircraft I build, I maintain a "construction" page for each

one in my "World War I Aircraft in 1:48 Scale" section. Click on

the link in the box below or go on to the "Camouflage Finish & Markings" section

below.

AEG N.I (C.IVn) CAMOUFLAGE

FINISH & MARKINGS

The basic camouflage finish for this

aircraft is a factory-applied, hand-painted four-color hexagonal night scheme

over the entire surface of the aircraft. I based the scheme on a Bob

Pearson color profile from Over the Front

11

Illustration 3: AEG N.I

Color Artwork by Robert N. Pearson, Over the Front, Vol. 23, Issue 4

The four-color palette consists of light green, mid-blue, magenta, and black as

shown in Table 4 below which shows a color swatch and the test wing I painted.

The paint used was Vallejo acrylics and the formulas I created are found on the

AEG N.I (C.IVn) Construction Page.

All Eisernes Kreuz insignia are matt black without the usual white outline.

The only other marking is the serial number in matt black on the fin.

Smaller instructional markings such as "lift here" and the weight table are in

matt black.

The secret to painting the hexagons was quite simple. I created an image

of hexagons from an old wargaming sheet. I sized it down to fit the scale

and printed it on Micro-Mark clear/blue backing decal paper on my HP laser jet.

Before applying the decal, I decided that one of the colors would be painted

over all surfaces which would eliminate having to hand-paint one of the four

colors. I chose the light green. Also, before applying the clear

hexagon decal, I decided early on not to glue any parts to the aircraft: wings,

horizontal tail, vertical fin and rudder, wheels, and ailerons. These were

individually hand-painted in light green over which the decal was applied.

I painstakingly painted each of the hexes in a pattern to match Bob Pearson's

profile.

Table 4: Paint Color Swatches

for the Hexagonal Camouflage used on the AEG N.I (C.IVn)

|

Vallejo Mix of VC0913 First Hexagonal Night Camouflage Color |

%20AEG%20N.I%20(C.IVn)%2005c.jpg) |

|

Vallejo VC0872 Second Hexagonal Night Camouflage Color |

|

Vallejo VC0856 Third Hexagonal Night Camouflage Color |

|

Vallejo Flat Black VC0997 Fourth Hexagonal Night Camouflage Color |

AEG N.I (C.IVn)

C.9378/16 FINISHED PHOTO

GALLERY

------------------------------------- FINIS --------------------------------------

FOOTNOTES

1

Gray & Thetford,

German Aircraft of the First World War, page 549, photo provided by Alex

Imrie. This source was published in 1962 and says simply, "No more than a

single prototype is thought to have been built". However, Peter M. Grosz

produced his Frontbestand in 1985 and 1986 in which "Class N" showed that there

were 2 at the Front in June 1918 and 9 in August 1918 (no reliable records

beyond those dates). Clearly, the Sablatnig was the intended replacement

for AEG N.I whose numbers were declining, 7 in June 1918 and only 4 in August

1918. It is also possible to assume the "Class N" machines were

phasing out entirely!

2 Leaman, Paul (compiler), Atlas of German

and Foreign Seaplanes: Sablatnig Floatplanes, Cross & Cockade International,

Summer 2010 Volume 41/2. The original German title Atlas deutscher und

ausländischer Seeflugzeuge is presently

being reproduced with new comments and photos by CCI in installments.

3 Pope, Stephen, and Elizabeth-Anne

Wheal, Dictionary of the First World War, page 452. As will be seen

further on in my discussion, strategic bombing took many twists and turns but

was largely limited by the technology of the day. Bombers could never

range far enough or carry enough of a load to be more than a sizeable nuisance

although others would argue otherwise.

4 Castle, Ian. London 1914-17: The

Zeppelin Menace, Osprey Campaign Series No. 193. This source does an

excellent job of historically reporting the specific events of the German

airship raids. Note: all airships bombing London were "Zeppelins" named

after a German manufacturer who built the majority of these giants. The

major manufacturer in Germany was the Schütte-Lanz

company but to the British people who endured these raids, they were all

"Zeppelins".

5

Martel, René. French Strategic and

Tactical Bombardment Forces of World War I, page 22. The

creation date is really an official GQG directive authorizing the creation of

the

1er Groupe de

Bombardment (GB 1) which

was formed up by December 1914. There followed the creation of three more;

GB 2 in December 1914, GB 3 in March 1915, and GB 4 in March 1914. Each

Groupes de Bombardment consisted of three Escadrilles each of six

aircraft.

6 Sumner, Ian.

German Air Forces 1914-18, Osprey Elite Series No. 135, pages 25-26.

7 Cuneo,

John R. The Air Weapon 1914-1916, page178-180. The author lays down the

reason for not following the doctrine of strategic bombing was a "diversion"

explained as: "The armies badly needed armed airplanes and the distinction

between an armed two-seater (with which the bombing squadrons were still

equipped) and the single-seater was not clear to the army headquarters: both

were "combat" planes". In other words, local army commanders all along the

Western Front were clamoring for aircraft to engage or "combat" enemy aerial

penetration over and beyond their front lines. This activity, they said,

frightened the troops and lowered moral because there were too few or no German

aircraft to contest them. It is true that the strategic bombing purpose

was "diverted" but, too me, the main reasons were the acknowledgement that the

two-seaters had insignificant bomb load capacity and could not fly far enough to

hit vital strategic targets. Since all of the two-seaters were C-Type

aircraft armed with a forward-firing Spandau and a flexible rear-firing

Parabellum, they were the only available reserve to counter enemy air activity

over the front.

8 Castle, Ian. London 1917-18: The

Bomber Blitz, Osprey Campaign Series No. 227, pages 18-36. Another

competent overall analysis of the Gotha bombing raids. The left-over

defenses from the Zeppelin attacks were allowed to lapse. In the time

between the cessation of the Zeppelin attacks and the first Gotha attacks, some

RFC squadrons and AAA guns were re-deployed to the Western Front. The

Gotha Raids were a great surprise to the British people. However,

London defenses and other likely Gotha target areas were brought up to strength

and improved and finally, in May 1918, the raids ceased altogether especially

because night fighter tactics and AAA were greatly improved. Thereafter, the

Gothas of Kagohl 3 were used to hit strategic targets at night on the Western

Front.

9

Grosz, Peter M. Archiv: Frontbestand.

The Journal of the Early Aeroplane "WWI Aero", issue108 (Feb

1986), page 69.

10

Grosz, Peter M.

AEG N.I (C.IVn) Rare Birds, Over the Front, Volume 23, Issue 4, page 362.

11

Pearson, Robert. AEG N.I, Over the Front, Vol. 23, Issue 4, inside

back cover.

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND RECOMMENDED READING LIST:

Castle, Ian.

London 1914-17: The Zeppelin Menace, Osprey Campaign Series No. 193.

Botley, Oxford (UK): Osprey Publishing Ltd, 2008.

Castle, Ian. London 1917-18: The

Bomber Blitz, Osprey Campaign Series No. 227. Botley, Oxford (UK):

Osprey Publishing Ltd, 2010.

Cuneo,

John R. The Air Weapon 1914-1916, Volume II of Winged Mars. Harrisburg,

PA: Military Service Publishing Company, 1947.

Gray, Peter and Owen Thetford.

German Aircraft of the First World War. London: Putnam & Company,

1962.

Grosz, Peter M. Archiv: Frontbestand.

The Journal of the Early Aeroplane "WWI Aero", issues 107 (Dec 1985) and 108 (Feb

1986).

Grosz, Peter. M.

AEG N.I (C.IVn) Rare Birds, Over the Front, Volume 23, Issue 4. League

of World War I Aviation Historians, 2008.

Martel, René. French Strategic and

Tactical Bombardment Forces of World War I. Translated by Allen

Suddaby, edited by Steven Suddaby. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press Inc,

2007.

Pearson, Robert N.

AEG N.I color profile, Over the Front, Volume 23, Issue 4, Winter

2008.

Pope, Stephen and

Elizabeth-Anne Wheal. Dictionary of the First World War.

Barnsley, Yorkshire (UK): Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2003.

Sumner, Ian.

German Air Forces 1914-18, Osprey Elite Series No. 135. Botley,

Oxford (UK): Osprey Publishing Ltd, 2005.

|

|

|

Jager Miniatures 1:48 Scale German Flight Crew |

GO TO?

© Copyright by George Grasse

%20AEG%20N.I%20(C.IVn)%2004.jpg)

%20AEG%20N.I%20(C.IVn)%2005c.jpg)

%20AEG%20N.I%20(C.IVn)%2021.jpg)

%20AEG%20N.I%20(C.IVn)%2022.jpg)

%20AEG%20N.I%20(C.IVn)%2024.jpg)

%20AEG%20N.I%20(C.IVn)%2025.jpg)